Tag:

- All

- Alap

- Gat

- Gharanas

- Raga

- Riyaz

- Talim

-

Reply By Guruji-

Acharya Brahaspatiji’s explanation – According to him there are thousands of sounds between basic Sa and the upper Sa. From amongst these, there would be 22 sounds which the human voice can reproduce. These are called shrutis. From amongst these, there are 12 shrutis which sound pleasant /madhur to the ear. These are called swaras.

-

Reply By Guruji-

The prevailing definition of the raga is रंजयति इति राग: (what pleases the mind is a raga). Personally I found this definition rather too general and not specific. Hence I developed the definition based on the structure of the raga rather than generalizing – as follows.

a. Raga (concept)

The musical scale contains 7 + 5 notes (7 shuddha and 4 komal & 1 tivra).From these 12 notes selected notes, minimum 5 are used to build up a melodic structure called a raga. It is believed that there are about 300 ragas. However, only around 50 are heard in performances. The lesser known and difficult to perform ragas are called achhop and anvat respectively.

b. Every raga has melodic centres, two of which include – one of principal importance and the other a little less important, called vadi and samvadi respectively. Notes which support vadi and samvadi notes are called anuvadi notes. Notes that are excluded from the raga structure are called vivadi notes.

c. Ragas with melodic movements centred in the first half of the scale (Sa to Ma or Pa) are called purvang ragas and the second half of the scale (Ma or Pa to upper octave Sa) are called uttarang ragas.

d. According to tradition, every raga has a definite time period for performance, during the time cycle of 24 hours. A large section of the music community accepts this concept. Some believe that the concept is scientifically based on an intimate relationship between sound and light.

e. Tradition also has it, that specific ragas are performed during specific seasons such as spring, monsoon, etc. e.g. Basant, Bahar, etc. in spring time and Miyan Malhar, Desh etc. in the monsoons.

f. It is generally accepted that there are 9 basic emotions (rasas), some of which form the essential ingredients of any performance in the field of music, dance and theater. Every raga therefore has a basic emotion (rasa) as an undercurrent of its exposition. It is however incorrect to believe that a complete raga exposition from alap to jhala is based on only one rasa. Allied rasas do play significant role in raga development, depending upon the area of the melodic development, or the speed and the tempo at which the raga is performed.

[Note: A melodic structure cannot be called a raga unless it is accepted / adapted by the music community at large.]

-

Reply By Guruji-

After the students have learned gats of a few ragas, they could be trained to identify different ragas as a part of taleem. In this connection the following should be noted.

a. Paltas of several ragas are available with the students. From amongst these, a few paltas of ragas like Bhairav, Todi, Yaman etc. could be selected and students should be trained to learn them by heart.

b. The teacher could sing aroha – avroha of the identified few ragas in akar (and not by notations) to test the ability of the student to identify the concerned raga.

c. Student should be taught simple vocal bandishes of identified ragas. On having learned such bandishes, the student should be able to relate the melodic movements of the bandish with the palta. As a result, they would be able to identify the raga of the bandish.

d. Students should be encouraged to identify selected ragas through listening to music recitals on the web (YouTube).

After the student have been able to identify a raga comfortably, competitions could be held between students to identify swar as well as ragas, using different devices.

-

Reply By Guruji-

An interesting topic is the relationship between 2 ragas having same notes. The following are my comments:

a. While the notes may be the same for 2 ragas (e.g. Bhupali and Deshkar), the aroha and avroha could be different.

E.g. Bhupali सा रे ग प ध सा सा ध प ग रे सा

Deshkar सा ग प ध प सा – ध प सा सा ध प ग – रे (weak -durbal) साb. As a corollary, vadi-samvadi or melodic centres are also different.

c. Timing of the day / night of presenting 2 ragas with same notes also differs (e.g. Bhupali is sung in the late evening while Deshkar is sung in the morning).

d. Rasabhav of 2 different ragas with same notes also would differ according to the time of the day when they are sung / played.

e. The speed at which the raga is unfolded, depends upon the rasabhav (e.g. Deshkar is unfolded at a speed faster than Bhupali).

Examples of such ragas are as follows-

Bhupali – Deshkar

Basant – Paraj

Bibhas – Reva

Shree – Jaitashree

Puriya Dhanashree – Gauri -

Reply By Guruji-

a. Sankirna raga, also called jod raga or mishra raga, is a concept to include two or more distinct ragas, making it into a single entity. Usually such a jod raga is composed of two ragas. However, in exceptional cases like raga Khat (original name is Shat) – six ragas are combined together to be rendered as one unit.

b. The composition of sankirna (jod) raga can be done in three distinct ways.

i. One raga in aroha and another raga in avroha

ii. Having one raga in the purvang and another one in uttarang.

iii. In this third method the performer uses his musical artistry to play one raga after the other in any part of the scale. This is done with great care to ensure that the rendering does not result into a patch work but the product appears to be a composite product with required musical value.c. When you combine two ragas for e.g. Basant Bahar, Jayant Malhar etc., a significant question arises, as to which raga amongst the two, should be given greater prominence. Hence in a raga like Basant Bahar, many musicians believe that raga Basant should be given greater prominence than the raga Bahar. In practice (according to my experience), it is noted that by and large, musicians apply this principle, i.e. the first name of jod raga is given greater importance.

d. Usually there is a common note in a jod raga which could be treated as a transition point for effortlessly moving from one raga to another. Shuddha Ma evidently could be the transition point for sliding from Basant to Bahar or vice versa.

e. Bandishes or compositions covering sankirna ragas require special ability of the musician as a highly competent composer. He / she should ensure that salient points of both (or more) ragas are duly covered in the structure of the bandish – not an easy task. It is evident that composers and performers (as noted earlier) should have sufficient knowledge of intricacies of both (all) ragas involved.

f. There is a concept of ragang raga. It is believed that certain ragas are amenable more easily to be combined with another raga to make a musical entity. Ragas like Bahar, Malhar etc. are examples.

Important

g. Sankirna, jod or mishra ragas should not be mixed up with the concept prakars of ragas. For e.g. raga Bhairav, Todi, Malhar, Sarang, Kanada etc., each have several prakars. This is a distinct section of raga classification. Some examples are Ahir Bhairav, Prabhat Bhairav, Nat Bhairav, etc. -

Reply By Guruji-

Regular Puriya when sung with komal Dhaivat becomes Din-ki-Puriya. Another way to understand this raga – Lalit without shudhha Madhyam. It is noted that komal Dha has a special treatment.

-

Reply By Guruji-

A raga called Yamani-Bilawal has been in existence since long. As Ustad Vilayat Khan started playing Yemeni (which no one else had performed earlier) with greater freedom of movement and abundant use of Madhyam, one can say that he invented it – of course with readiness to face contradictions.

-

Reply By Guruji-

Many years ago, I had the occasion to discuss with a well-known painter the issue of pictorial representations of raga swarup. I learnt that majority of raga paintings are miniatures. Fortunately we had bought a set of what they call ‘ragamala’ miniature paintings of six ragas. It was noted that ragas like Darbari, which is commonly known to project grandeur, a painting of which covers an old king gradually retiring with slow gait into vanprasthashram. Similarly raga Shree, with a sharp Rishabh conjoined with a ‘Pa’, creates a singular atmosphere. The painting of this raga shows that a young warrior with an open sword, with arm raised, has a vivid red colour in full background of the painting. Frankly, I could not match the picturisation of other ragas in the paintings. Hence it appears that all painters, who have artistically painted the ragamala paintings, have done so according to their own impressions of the atmosphere / mood that a particular raga creates. The painting therefore is purely based on painter’s vision. It is possible that the painter might have consulted some musicians in this regard, but as mentioned earlier, I could not match paintings of other ragas with the painter’s assessment. I think one can take this issue on its face value and leave the ragamala paintings, as a form of art, which need not relate to a common musicality. From the above it could be concluded that there cannot be a common denominator of pictorial impressions of a raga, painted by different artists. Hence, philosophical dictums like, राग के दशŊन करो have spiritual values which enable musicians to venerate raga music with Godly values.

-

Reply By Guruji-

टोड़ी

टोड़ी के है प्रकार पंदर

खंड है दो जिसके अंदरमध्यम तीव्र और मध्यम वर्जित

ऐसे है दो खंड सही सर्जितमियाँ की, गुजरी, बहादुरी और खट टोड़ी

सबमे तीव्र मध्यम है जब जोडीबिना तीव्र मध्यम के खंड में, जौनपुरी है जमीन

छे टोड़ी प्रकार बनते है उसबिनकरो कोमल रिषभ, बने कोमल आसावरी

भाव करुण और चाल है हरीभरीलगे दोनो गांधार, तो बने देव गांधार

और दोनो रिषभ जौनपुरी में, बने गांधारी रसदारजब जौनपुरी मे दोनों गांधार,

बने लाचारी टोड़ी सुधारऔर जब जोड़ो दोनो रिषभ,

तब बने लक्ष्मीं टोड़ी सहजभूपाली, बिलासखानी और देशी

ये प्रकार तो आते है सबको सहीएक ही बाकी प्रकार है हुसैनी टोड़ी

वो तो नहीं समझे तो खुश नसीब -

Reply By Guruji-

Reva has the same aroha/avroha as Bibhas, ie. S R G P D S-S D P G R S. In Bibhas, the komal Rishabh and Dhaivat are akin to Bhairav, and the same are Shree based in Reva. Bibhas is a morning raga while Reva is an evening raga.

kesehatan- At this time it seems like Expression Engine is the preferred blogging platform available right now. (from what I've read) Is that what you're using on your blog?

-

Reply By Guruji-

A thaat is a division comprising of specific ragas. This system was evolved by Pandit Bhatkhande, who was a keen musicologist. He divided ragas into 10 divisions, each comprising a specific list of ragas which are similar / have the same notes. If we go according to the time theory, then the names of the ragas starting from early morning to late night could be (1) Bhairav (2) Bhairavi (3) Asavari (4) Todi (5) Bilawal (6) Kafi (7) Khamaj (8) Purvi (9) Marwa (10) Kalyan. All the ragas have been tabulated under these headings denoting the 10 thaats. This could be treated as a general guideline and not something which is sacrosanct.

Pandit Bhatkhande also noticed that several ragas are known by different names and had different structures in different parts of the country. Hence, he convened a meeting (in 1928) of all known musicians and music related personalities, to discuss how to standardize the raga system. Different opinions with regard to the names of the ragas as well as their structures were expressed during the meeting. After obtaining concurrence of all the entities, Bhatkhandeji could succeed in having a common nomenclature for different ragas.

With regard to their structures, he could get an agreement from the musicians that the different versions of a raga, could be described as prakars of that raga. Example, Desi Todi – with shuddha Dha, with komal Dha and both the Dha’s – three prakars of Desi Todi. This was a very valuable work and the resultant classification has been accepted by the music fraternity.

-

Reply By Guruji-

Note patterns of the above mentioned ragas are not identical. The aroha and avroha are also distinct. Though notes of these ragas are same, one version of Adana does not have komal Dhaivat. The vadi/ samvadi or melodic centres of the mentioned ragas are distinct and different. It is accepted that Adana was created to fecilitate execution of taans, as in Darbari andolit Gandhar and Dhaivat created execution problems.

Shuddha Basant has several versions in different gharanas. Melodic movements of the mentioned ragas, are required to be performed in uttrang/ purvang per the rules. As is known taans are catagarised in different prakars. Hence suitable taan prakars are performed. -

Reply By Guruji-

a. There are a few movements in a raga which could be construed as belonging to a similar raga. What I have noticed is that the preceding or following movements of a questionable phrase could remedy the situation.

b. I feel that such an introduction of an alien note could have been done by a master musician (Ustad Enayet Khan introducing komal Gandhar in Tilak kamod). This could have been followed by musicians and turned into a prakar.

c. I feel that introduction of such notes are done by noted musicians to ensure release of tension and create an element of surprise. Perhaps the need for such relief could have been felt when the raga has been performed upto antara section, i.e. in tar saptak. I have noticed that musicians introduce komal Gandhar after creating tension through enabling movements in Raga Desh. Even in raga Dhani, shudhha Rishabh is introduced in tar saptak. -

Reply By Guruji-

To start with, it is important to understand that in my opinion there is a connection between sound and light. I believe that the time theory of ragas would be based on this concept. Without getting technical, I would divide the time zones during which particular identified ragas could be / should be played, would depend upon the intensity of sunlight. In other words, i.e. the angle at which the Sun’s rays are touching the ground. To explain further, when night ends and morning starts, there is a period when the Sun has not yet arisen, but there is ujala (light) – this section is known as dawn. In technical language, it is known as sandhiprakash samay. Similar period exists in the evening, when the Sun has gone down (dusk) but there is still some visibility (light). This period is also known as sandhiprakash samay. It is believed that both these periods are very sensitive, during which specific recommended ragas should be played / sung. Hence I would divide the time zone in the following manner:

a. Early morning – sandhiprakash samay prior to 5 / 6 am: Bhatiyar, Bhankar, Kalingda, Lalit etc.

b. When the Sun has just risen and its rays are very soft – 6 am to 9 am: Ahir Bhairav, Bhairav, Bhairavi, Bilaskhani Todi etc.

c. The Sun has risen farther and the rays are projected with an angle of 45 degrees from the earth – 9 am to 11 am: Jaunpuri, Desi Todi, Gujari Todi etc.

d. Further period would be when the Sun’s rays become more intensive at an angle between 45 to 70 degrees – from 11 am to 1 pm: Alhaiya Bilawal etc.

e. Further period could be when Sun’s rays are between 70 to 90 degrees from the earth (noon time) – from 12 pm to 3 pm: Gaud Sarang , Shuddha Sarang, Brindavani Sarang, Madhmadh Sarang etc.

f. When the Sun starts going down and the rays are at an angle between 90 to 120/150 degrees – from 4 pm to 6 pm: Bhimpalas, Kafi (and its prakars), Khamaj, Madhuwanti, Multani, Patdeep, Pilu, Puriya Dhanshree, Barwa, Marwa etc.

g. The Sun has gone down completely but the darkness has not yet set in. This would be the sandhiprakash or twilight zone – from 6 pm to 7 pm: Shree, Gauri etc.

h. After around 6-7 pm, when the night period starts and the identified time zone could be from 6-7 pm to 9 pm: Bhupali, Yaman, Shyam Kalyan, Gorakh Kalyan, Hansadhwani, Jaijaiwati, Kalawati, Puriya, Maru Bihag, Milya Malhar (can be played anytime during monsoon season), Desh, Jhinjhoti, Jog etc.

i. The last zone would be from 9 pm upto midnight – extended upto dawn in the morning: Abhogi Kanada, Bageshri, Rageshree, Bihag, Darbari Kanada, Kedar, Malkauns, Chandrakauns etc.

Notes:

A. In a seminar held sometime back, there was a general opinion that flexibility of 3 to 4 hrs could be given in observance of time theory, especially, as concerts are held in the evening and very rarely in the morning. There was a time when concerts started (in many cities) around 9.30 pm and went on until early hrs of morning. This gave scope to play late night or early morning ragas.

B. I have listed about 50 ragas which students may be actually playing / receiving taleem for. Amongst this, there are some ragas which the professional (very senior) students are playing / could play. -

Reply By Guruji-

a. Both these ragas belong to so called Purvi thaat.

b. According to some, there are 13 fairly known ragas in this thaat, Purvi being the thaat raga.

c. This leaves 12 ragas, out of which, 4 are achhop ragas which are – Tanki, Malvi, Triveni and Deepak.

d. Balance 8 ragas can be structured into 4 pairs each having 2 ragas with similar notes.

These are:

i. Reva/Bibhas

ii. Shree/Jaitshree

iii. Gauri/Puriya dhanasri

iv. Paraj /Basant.

e. The main difference between Purvi and Puriya Dhanashri is:

i. The use of shuddha Madhyam in Purvi.

ii. Aroh in both ragas is almost the same except that Puriya Dhanashri does not move as Dha-Ni- Sa but Dha-Ni-Re- Sa

iii. Ni- Re- Ni-Dha- Ni with both starting and ending Ni, in lower octave, is the catch phrase in Puriya Dhanashri.

f. Use of shuddha Madhyam in Purvi can be:

i. Pa- Ma (tivra)-Ga- Ma- Ga or

ii. b. Pa- Ma (tivra)- Ga- Ma- Re- Ga or

iii. c. Pa- Ma (tivra) Ga- Ma – Re- Ma- Ga.

Some take the liberty of using Pa- Ma (tivra) Ma- Ga.

g. Essentially Purvi moves around Gandhar while Puriya Dhanashri moves around Pancham.

Please note: Shree pairs with Gauri and Puriya Dhanashri pairs with Jaitshree.https://Casinovavada.Blogspot.com/2021/12/blog-post_22.html- What's up friends, how iis the whole thing, andd what you want to say about tgis paragraph, in my view its really amazing designed for me. Also visit my blog - https://Casinovavada.Blogspot.com/2021/12/blog-post_22.html

casinoonlinevavada.Onepage.website- This paragraph gives clear idea in fasvor of the new visitors of blogging, that in fact how to do running a blog. Also visit my homepage ... casinoonlinevavada.Onepage.website

https://Telegra.ph/Mobile-online-casinos-10-23- I was recommended tis web site by means of my cousin.I am now not certain whether this submit is written through him as no one else know such precise about my problem. You are wonderful! Thanks! my web-site https://Telegra.ph/Mobile-online-casinos-10-23

-

Reply By Guruji-

To me, Shuddha Basant seems like Lalit with shuddha Dhaivat. The raga revolves around shuddha Madhyam. In Uttarang, movements Dha Ni Sa Ni Dha Ni gives a tinge of raga Kaushik Dhwani. Some musicians play with Pancham which gives a shade of Bhatiyar. Not difficult to play but doesn’t seem to be very commonly played.

-

Reply By Guruji-

Yes, and there could be some variations too.

-

Reply By Guruji-

No. However some do use a touch of komal Ni just as we touch komal Ga in tar saptak in Desh. I have however heard some old gats in Tilak Kamod using komal Ni as a regular note. This variety is very rarely heard these days. Desh and Tilak Kamod have same notes except that Desh has an extra komal Ni. Aroha (not the chalan) in same in both these ragas. While Desh in avroha descends straight Sa-Ni-Dha-Pa-Ma-Ga-Re S (all notes are shuddha), Tilak Kamod has quite a vakra movement in avroha – specially in the middle octave. Desh has a touch of sombreity, Tilak Kamod has a more direct matter of fact approach. Both are frequently used in light classical music.

-

Reply By Guruji-

Aroha-avroha of Shiv Kalyan : except नी॒ (komal) all other notes are shuddha सा रे ग प नीसा – सा नी प ग रे सा || The chalan would be as follows: Aroha – नी सा रेग रेसा सा रेग प ग रे ग प नी सा ||

Avroha – सा नी प ग रे नी प ग रेसा || Vadi-samvadi, though I do not believe in this concept and I find the terminology of melodic centre or ठहरनेकी जग़ह as follows : ग प and upper सा -

Reply By Guruji-

Yes, it is true that whilst a substantial number of ragas can be elaborated / unfolded during alap portion, there are some ragas which require coverage of several notes to project the raga swaroop of the concerned raga. There are several reasons of this as follows:

a. A majority of ragas reveal their swaroop in a few notes and hence a systematic unfolding of the raga in the alap stage can be undertaken on a step by step basis (silsila based badhat). In such ragas, it would be possible to start the alap utilizing सा as the base and unfolding the raga swaroop through a few notes including treatment of a couple of notes below सा and a couple of notes above सा (e.g. raga Puriya, Yaman, Jog etc.)

b. For some ragas like as Jaijaiwanti, Puriya Kalyan, Bihag, Desh, Pilu etc. they cannot be treated in line with ragas mentioned in para 1. It is not possible to fully reveal the swarup of the raga and one is likely to misinterpret the same. For e.g. in Bihag, if the melodic movements are नींसा – नींरेसा – प नी – प सा These phrases could indicate several ragas like Desh, Khamaj, Sarang etc. Therefore it would be necessary to start with phrases like नींसा followed by a meed / murki रेग म ग रे. In this manner, it would be easy to ascertain that the raga is Desh. Thus, in such ragas therefore, it would be essential to have more than one melodic movement to determine the raga.Conclusion: As would be noted therefore, it is swaroop of the raga which determines whether one can develop it on the basis of silsila or expand the melodic area to cover several phrases.

-

Reply By Guruji-

To start with I do not believe in the importance of the thaat system. Every raga is a thaat in itself as earlier it meant a scale. Suppose Deshkar belonged to the same thaat as Bhupali, would we play it differently? As long as you are keenly aware of the authentic swaroop of a raga, the concept of thaat system is of no value or significance.

-

Reply By Guruji-

According to Ustad Faiyaz Ahmed Khan, the difference between an alankar and a taan is that in alankar the melodic phrases progress step by step in straight sequence while in a taan melodic steps progress with intermediate omissions of steps. However, alankaric taan is also considered as a prakar of taans. Some gharanas use this prakar in their renditions. Again, often alankar based gliding phrases are used by vocalists to sum up the ending of taan patterns, as a kind of samet to arrive at the sam. Hence, there is no special position for alankar based taans.

-

Reply By Guruji-

a. As you know, mixed or jod ragas are structured in three ways:

i. one raga in aroha and another in avroha.

ii. one raga in purvang and another raga in the uttrang.

iii. freedom to change from one raga to another raga, in a manner which maintains the true swaroop of each raga- the mix being conducive to enhancing overall beauty of the presentation.

b. Desh Malhar is a jod raga of Desh and Miya Malhar. Usually Desh is in purvang and Malhar is in the uttarang. Change from one to another has to be melodically correct and subject to not over-emphasising one as compared to the other. -

Reply By Guruji-

Desh has only shuddha Ni in aroha while Malhar has both komal and shuddha Ni in sequence –Ni (komal) Dha Ni (shuddha) Sa. Sometimes, chalans may differ from gharana to gharana.

-

Reply By Guruji-

a. Thaat system as is well-known, was created / established by Pandit Bhatkhande ji. It has been acknowledged that he contributed greatly to the cause of Indian music through his collective efforts to standardize both the content and nomenclature of the prevailing ragas.

In my opinion, thaat system is essentially meant for a general understanding of categorisation of ragas divided into 10 thaats. However there are exceptions. There could be some examples of fitting ragas like Madhuwanti in one of the thaats. I recollect very well that in olden days a sarangi player would ask the main vocalist ‘in which thaat he should tune his instrument’. This implies that prevalent definition of a thaat was related to the scale of a raga.

To conclude, I would recommend that it is good to know details about the thaat system and the classification of the ragas according to the same. However, the focus should be on individual ragas – and individual ragas only, and not on the thaat to which the concerned raga belongs according to Bhatkhande ji’s classification.

b. Vadi/samvadi concept: whilst this concept may be of some value to the students of music, it is useful to know the basis, to start with. However, my assessment is that whilst a musician is developing a raga – especially in the alap, he/she does not give greater importance or emphasis to the vadi note of the concerned raga as compared to the samvadi note. Some of the musicians are not bothered about thaat of the raga, they just develop the raga according to their taleem. Such taleem that I referred to, translates itself into resting on significant notes whilst developing a raga. Ustads used to call such notes as ठहरनेकी जगह . I would like to call them melodic centres. Each centre has its own value, neither lesser nor greater than the other. There could be more than 2 centres in ragas like Yaman, where we have Gandhar, Pancham and Nishad as resting points (ठहरनेकी जगह) or melodic centres.

c. Aroha / avroha: as explained earlier, the concept of aroha / avroha is essentially meant for students of music. Just as the chaste language, over a period, changes itself in to a colloquial language, so also aroha / avroha concepts change into what we call as chalan. Not only that chalan partially simplifies the concept of aroha/ avroha but is used by musicians to have calculated freedom from the strict tenets of aroha/ avroha concepts. In my opinion, musicians who follow aroha /avroha strictly would be called “kitabi gavaye (bookish musicians)”.

-

Reply By Guruji-

To start with let us note that sister ragas like Rageshri and Kaushik Dhwani do not have Pancham in their scales. I assume that perhaps earlier Pancham may not be a part of Bageshri scale but was later introduced by great musicians to enhance its beauty and increase the scope for additional melodic movements.

-

Reply By Guruji-

Why would you like to miss the described advantages? In any case Pancham is hardly included in developing alap in the lower and middle octave upto Madhyam. It is only after the music community accepts the change if any, that it becomes a part of the chalan of the raga. Even if the first initial is not a capital for proper nouns, people will recognise the intent. Similarly if you do not use Pancham in Bageshri chalan, people will still recognise it as Bageshri with a remark that the musician’s grammar seems to be weak !!!

-

Reply By Guruji-

Great minds have noted that many phenomena occurring in human surroundings have a cyclical movement i.e. a movement ends where it starts from. To give an example – Tintaal played on tabla completes its cyclical movement at a point from which the tala starts a new cycle.

To further support this contention, we could take example of vocal bandishes. By and large, these bandishes have 4 lines namely mukhda, manjha, antara and amad. Usually, the mukhda comprises of the essence of the raga swaroop, while the manjha goes down into lower octave. The antara takes the melody to upper Sa and amad brings the melodic cycle back from where the mukhda started, completing a cycle. Sitar gats, both vilambit and drut, also follow the same structure.

To further elucidate this concept, the development of alap in vocal music and now followed by instrumentalists of specific gharanas, has a cyclical pattern. To illustrate – there are four stages in alap development – namely sthayi, antara, sanchari and abhog. As we all know, sthayi is concerned with melodic development from lower octave up to the midpoint of the scale, while antara is concerned with the development from midpoint to upper octave. Sanchari (following dhrupad discipline) covers movements through phrases interspersed with sweeps. The melodic movement is played at slightly faster pace than the alap covering all these sections. Abhog, the last section, is designed to bring melodic movements from the upper octave to the lower octave – called amad in musical language. Thus, it is noted that, alap starts in sthayi portion followed by antara and sanchari, and ends with amad, which completes a cycle.

-

Reply By Guruji-

Students are already aware of the technical aspect of merukhand viz. possible permutations and combinations of seven basic notes of an octave. We are aware that the number of combinations could be as follows.

No. of notes – Combinations

1 – 1

2 – 2

3 – 6

4 – 24

5 – 120

6 – 720

7 – 5040e.g. for 3 notes e.g. for 4 notes सा रे ग सा रे ग म सा रे म ग सा ग म रे रे ग म सा रे सा ग रे सा ग म रे सा म ग ग सा म रे ग रे म सा सा ग रे सा ग रे म सा म रे ग सा म ग रे रे म ग सा ग सा रे ग सा रे म म सा रे ग म सा ग रे म रे ग सा रे ग सा रे ग सा म रे म सा ग ग म सा रे ग म रे सा ग रे सा ग रे सा म म रे सा ग म ग सा रे म ग रे सा It is essential to understand that the concept of merukhand as above cannot be mechanically utilized for developing alap. Hence, only the concept of permutations and combinations could suitably (melodically) be used in developing alap (especially in Kirana gharana style), in the following manner.

As explained earlier, to start with, one has to establish the zamin (foundation) of Sa – hence short / brief melodic phrases could be introduced ending on Sa. It is evident that we are not building a design / subject and hence the melodic movements should cover short phrases within the confines of raga swaroop.

Once the foundation has been established and raga vistar has started, the concept of merukhand could be utilized gainfully in the initial stages of alap, e.g. from Sa to lower octave Pa. The melodic movements could be guided by starting with Sa and reaching the lower Pa with an appropriate movement. The next could be, moving from lower Pa to Sa, the musical journey being guided by raga swaroop and suitable designs, which are musically appealing. This approach can be carried out a few times, after which the resting point would be the lower Pa.

Now starts the journey of subject building. The concept for subject building comprises of a melodic movement with a short phrase ending at a melodic centre, in keeping with the stage at which the alap has been unfolded. (Students have already been explained that, during alap, the stages of development must ensure that the melodic movements end at a melodic centre depending upon the stage of development). The melodic movements must be so designed as to give different combinations – not mechanical like merukhand but musically appealing and forming grammatically appropriate musical movements ending with the contemplated subject.

In this manner, we reach the upper Sa, after developing melodic movements through subject building on each melodic centre of the concerned raga. It is essential to note that to return to the basic Sa after developing treated melodic movements ending with upper Sa, the approach should be silsila based (methodical) to return step by step to the basic Sa from where the alap had in reality started (the wapsi or return).

After the basic alap is completed, there will be two stages of development viz. sanchari and abhog. As we are dealing with the role of merukhand, I do not think it has any role to play in these two developments.

Whilst ensuring that various melodic movements in all the above mentioned expositions would be subject to several permutations and combinations, the execution could be made more effective by following the tenets of adding novelty in the following manner.

a) Volume variation

b) Speed variation

c) Using concept of gaps

d) Selective use of decorative elements like murkis etc.

and lastly

e) Unexpected phraseology. -

Reply By Guruji-

Further to my note on the subject of alap, in the following you will find an analytical study in bullet points, which reveals the technical part.

● Alap developed in two patterns:

⮚ Melodic

⮚ Geometric● Both are used to build a subject – a paragraph – in the musical statement being unfolded.

● Techniques used to beautify both the above-mentioned patterns:

⮚ Observe correctness of raga swaroop

⮚ Ensure inputs of emotional content suitable to the raga and specific section of the unfoldment and related ideas.

⮚ Vary speed of execution to convey specific ideas and make phrases more vocal oriented and sustain interest.

⮚ Introduce rhythm based phrases.

⮚ Vary volumes in keeping with, and in contrast to, already executed phrases.

⮚ Use of decorative elements i.e. murkis and meends to suit the mood and relate to vocal techniques.● Unfoldment of raga swaroop in alap stage has to follow silsila or system prescribed in our gharana – basic elements of which are as follows:

⮚ Zamin or foundation note – Sa to be established and projected at the beginning and at different stages of unfoldment or badhat.

⮚ Technique of badhat – building up prescribed melodic centres.● Observe different sections or stages of alap, viz:

⮚ sthayi

⮚ antara

⮚ sanchari

⮚ abhog -

Reply By Guruji-

As is well-known, recitals of plucking instruments normally cover 4 stages viz. 1) alap 2) jod 3) gat / taans 4) jhala.

Usually in vocal music (khayal) alap is rendered along with theka, whilst instrumentalists by and large, follow the dhrupad structure where alap is executed without any accompaniment on pakhawaj / tabla. Thus, in case of dhrupad and a large section of instruments, alap and jod are performed without the rhythmic accompaniment.

By and large, instrumental music follows alap silsila with inspiration from different gharanas of vocal music. Our gharana follows Kirana gharana concept of alap development. The silsila or system of alap in this approach has various important features / techniques, which play a significant role in unfolding a raga in a systematic manner. These are as follows.

a. Develop Sa as a foundation (zamin) of the raga structure. It is from Sa that the entire raga structure is developed / built.

b. Subject building – once the alap unfolding covers 3 or more notes, the musician has the opportunity to introduce the technique of subject building.

c. Substantial use of murkis in the melodic structure is believed to be derived from the techniques used by sarangi players.

d. System of introducing an additional note within the raga swaroop whilst unfolding the raga is undertaken according to special rules.

e. Whilst building melodic centres during the unfoldment of the raga, the technique of volume variation according to importance of the note is undertaken. The importance of each note is described as balwan (dominant), saman (equal) or durbal (weak). -

Reply By Guruji-

It is a well-known that a few decades ago, sitar had 7 strings including 2 jod strings and a lower Pa string of brass. Over a period of time, 1 jod string was removed. This resulted into following benefits.

a. This created a greater gap between baj string and the balance jod string. This facilitated stroke production without creating a jumble of sounds from 2 jod strings, as was experienced earlier.

b. Ustad Vilayat Khan did not require a tanpura player to accompany his public sitar recitals (apparently as per earlier practice). However, he discreetly evolved a technique which assists in creating an atmosphere like tanpura strumming. Details have been explained in the note on ‘Role of chikari’.

c. It has been accepted fact that the space between two melodic phrases should ensure that the recital does not become hasty and tense. Playing chikari with a gliding stroke followed by pluck on the jod string ensures that a musical space is created. The speed at which alap is to be executed, should be in consonance with the mood of the raga. Thus the speed at which alap could be executed is regulated.One additional point. The plucking of the jod string should not be sharp but soft and rounded – similar to the plucking of tanpura strings, which is not done with the tip of the fingers but with the fleshy part, to achieve rounded sound merging with the overall resultant composite musicality.

-

Reply By Guruji-

Starting from main (Madhyam) string, the last two strings are chikari strings. This is a result of deep thinking and profound consideration of sound when main chikari is tuned to Sa (Shadaj) and the small chikari is tuned into upper Sa (Shadaj).

It is essential to understand the role of chikari plucked during alap, jod and jhala. Though such plucking is essentially meant to give support to the main string melody, such required support varies in different sections – details are as follows.

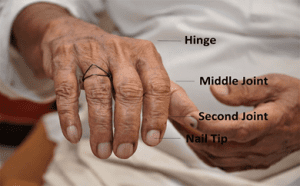

Before we consider different methods of plucking chikari strings, it would be necessary to understand the sources of strength which produce the pluck. Referring to the photograph, the main joint is only a hinge (mijagra) and not a source of strength. It would be noted that, there are 3 main sources of strength for plucking chikari strings.

a) During the alap, it is essential to maintain a tanpura like support, hence plucking of chikari string should not be a straight pluck but a glide from chikari strings to Gandhar & Pancham strings, followed by a pluck of the jod string. Such 2 plucks i.e. chikari along with jod create a tanpura like atmosphere – a great support to the main alap movement. To produce such tanpura like ambiance, the source of strength for plucking chikari should emanate from middle joint (refer to the photo).

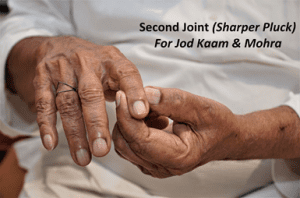

b) For playing jod patterns, the chikaris are not expected to create tanpura like atmosphere but to play a role to accentuate beats used in jod execution. In fact the jod, I assume, is known by its name, as the rhythmic patterns are 1-2, 1-2 etc. The number 1 begins with main string and number 2 begins with chikari string. The source of strength for creating the required sound from the chikari should be as per second joint (refer to the photo).

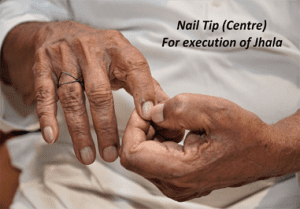

c) For the jhala section, it is evident that a pattern of 1-2-3-4, 1-2-3-4 etc. is to be created. To match with the tabla theka, all beats (4) have to be of equal volume / sharpness to create rhythmic patterns creating spiritual or inward looking effect. With the required sharpness to pluck, the chikari string should utilize the strength arising from nail tip centre (refer to the photo).

-

Reply By Guruji-

When you are giving a public recital, you have five techniques to make the expression more effective.

1) Volume variation

2) Speed variation

3) Gaps between phrases

4) Intelligent use of decorative elements

5) Unexpected phraseologyIn a public recital the performer attempts to partially, if not fully, impress the listeners with his/her musical prowess. Playing for ‘self’ is a different phenomenon.

-

Reply By Guruji-

As is well-known, the role of sitar subsequent to its invention in the 18th century, was what is called purak baj. It is believed that the role of sitar was to fill up the gaps which occur during recitals of qawwali singers. It was the role of sitar players to fill these gaps with strokes dir dir dir dir, executed with the right hand, while the left hand remained stationary on a note suitable to the melody. Thus, it was called purak baj.

With musical and stylistic evolution, the role of left hand had also to become more active, which resulted into small pithy phrases being played by the left hand, duly supported by the right hand. Over a period, the left hand became increasingly active and started playing melody on its own. Hence, right hand and left hand started executing music on sitar in tandem.

It is only since the first decade of 20th century that records of instrumentalists are available – Ustad Imdad Khan’s (1848-1920) records published in 1904 (about 14 sides) appear to be the first instrumental music records available. In these recordings, it is clearly noticed that while the right hand is playing a dominant role, left hand is also moving fairly dexterously. However, right hand still seem to dominate the recital.

Even sarod gats which we had the opportunity to listen to subsequently, also indicated the same situation, as the right hand was playing a dominant role. Colloquially, compositions played on plucking instruments were called gats and on other bowing instruments, such as sarangi etc. were called bandishes. This is a general statement as my observations in this note refer mainly to, plucking instruments with a focus on sitar.

It was in Ustad Enayet Khan Saheb’s (1894-1938) style, that we note from his several records, that the left hand is almost equally relevant compared to the right hand which resulted into the “divine music” – he being called ‘Bengal ka Jadugar’. It is also noted that, in addition to the bol patterns of Ustad Imdad Khan’s gats, Ustad Enayet Khan’s gats also revealed a specific bol pattern, especially for drut gats.

It was thus – as far as sitar is concerned – left to Ustad Vilayat Khan to assimilate gats of his forefathers and add a flavour of gayaki ang, which made the gats composed by him, highly lyrical and displayed considerable affinity to the compositions of vocal music. His gats can be divided in three categories –

a. Gats with main stay of right hand bols – left hand playing relatively a simple role.

b. Later a change occurred in which the right hand and the left hand together, played a role with contribution of 50% each. In other words, vocalized style and instrumentalists’ style played equal roles.

c. Still later, the gats display the left hand contributing almost 70-80% of the gat compositions while the balance was executed by the right hand – just to support the vocalized idiom.Conclusion

Therefore, we notice that from a purak baj where only the right hand was relevant – over a period i.e. up to Ustad Vilayat Khan style, the vocalized idiom, i.e. the left hand played significantly important role in the formation of sitar gats. -

Reply By Guruji-

Barring some exceptions, a bandish (vocal music) and a gat (instrumental music) has four lines.

a. The first line or an introductory line is usually called mukhda in vocal music and a gat in instrumental music (though the entire structure is also called a gat).

b. The second line is called manjha – originally called madhya – which means a middle line.

c. The third line is called antara

d. The fourth line is called amadFollowing the principle of several contemplated activities, a bandish or a gat follows a cyclical structure /tenet. The first line is the starting point, the manjha takes the melody into lower octave, the antara takes the melody to upper octave and the amad bring you down to the point where the composition started, and thus completes the cycle.

Just as the melodic movement of the bandish / gat is circular in motion, the literal content (sahitya) of a bandish (vocal music) also has similar unfolding, for instance –

अब गुमान मन नाही करिए

जो सब गुनी जन कहे चित्त धरिए |

ध्यान ग्यान सुर ताल पहले

वाको साधन करिए धरिए ||It is noted that the literal content starts with a philosophy including respect for Guru. The antara portion takes the theme further with an advice to aspiring musicians. It is evident that the bandish starts with mukhda and continues further through manjha, antara and amad to complete the narration.

-

Reply By Guruji-

To start with, we should note that a tihai is made up of three identical phrases played one after the other to reach the sam (1st beat of the tala cycle) or in some cases to reach the matra from where the mukhda or the gat starts.

Why is tihai made up of three phrases? Number 3 seems to have a very significant and effective reason. Apparently no satisfying explanation of why this magical no. 3 is frequently used to describe important entities. There are many examples relating to number 3 (a) Brahma, Vishnu, Mahesh (b) akash, prithvi, patal etc. I was just wondering whether the logical number of 3 could be based on 1 + 2 on which (according to some) entire mathematics is based.

The role of a tihai is to fill the gap of matras between ending of a taan and the distance from that point to the sam, in an artistic manner. Thus a tihai is an adjunct to a taan and not the main focus of the overall melodic expression. In other words, a taan is not played as an adjunct to a tihai but other way round.

Whether it is musically more satisfying if a tihai is composed on the spur of moment and not fixed in advance, is an interesting question. However to improvise in such a manner, the performer has to be capable enough to do so. No doubt, prefixed tihais becomes mechanical and hence are not as satisfying.

Tihai in gat

Apart from the role of tihai in relation to taan, it has been noted that some earlier drut sitar gats also occasionally used tihai as an ending part of the gat. It is very important to note that such tihais are not introduced in the sthayi portion of the gat but only in the antara section. It stands to reason therefore that when a tihai is used after execution of taan at the end of taan – as an adjunct, it could be argued that the use of tihai in drut instrumental gat is also woven into a fag end of the antara portion. In my long career, I have never come across a gat having a tihai in the sthayi portion.Chakradhar tihai

This type of tihai are seldom used by contemporary sitar players. I know a few of chakradhar tihais which U. Vilayat Khan used to play as a part of gat development – especially in taan portion. However, these tihais were not an adjunct to a taan but had a complete melodic structure of their own. -

Reply By Guruji-

Masitkhani being a slow tempo gat, could be easier to teach/ play…. but the tempo is difficult for students to absorb with hand clapping. Hence it is better to start with a Razakhani gat in a slower tempo and then gradually increase the tempo. Further, it is easier to remember a faster moving melody than a slow long drawn melodic structure. However, my response relates to a beginner and not a relatively advanced student.

-

Reply By Guruji-

Though I have attempted to get precise information with regard to the difference between sarod gats and sitar gats, I have not succeeded. I have also heard an opinion that there is no difference. Keeping in view that though both the instruments are plucking instruments, the technique of actual music making differs as follows:

a. Whilst sitar has a fret board with frets, sarod does not have any frets and the musician is obliged to identify correct notes from the plain surface.

b. The plucking of strings in sitar is with a mizrab, while sarod players use, what is called, jawa.

c. Further, what is ‘da’ in sitar is infact ‘ra’ of the sarod. This is because the outgoing stroke of a jawa of sarod is from the inside to the outside of the string (in a sense, like the forehand of a tennis player). The inward stroke is relatively weak, hence the outward stroke in sarod is called ‘da’, while the inward stroke is called ‘ra’. On the other hand, in sitar, the inward stroke, which is the main stroke, is called as ‘da’ and the outward stroke is called ‘ra’. In other words, ‘da’ and ‘ra’ of both these instruments are different.

d. With this background, I tried to analyse the difference between the gats of these two instruments after hearing as many gats of sarod as possible. I found the following differences:

i. Sitar gats use the bol ‘dir’ extensively, while sarod gats use the bol ‘dra’ in many of the gats.

ii. I have noticed that sarod gats are relatively longer than sitar gats.

iii. Main line (mukhda) of the sarod gat takes several avartans to complete. In many of the sitar gats, the main line are completed in one avartan. -

Reply By Guruji-

I have always maintained that Masitkhani gats have fixed bols, and are played in vilambit laya. But in recent times, there are several new compositions in vilambit laya with varying bols. Correctly these cannot be called as pure Masitkhani gats. On the other hand, it is noted that all Razakhani gats do not have a fixed bol pattern. In some compositions the gats, instead of starting from 7th matra, starts from 13th matra with the same bols. There are several other gats based on different bol patterns. But they are all still called as Razakhani gats. In my opinion, Razakhani gats were evolved on the basis of Bandish ki thumri. This concept however is now pushed into the background and gats are considered as vilambit or drut along with the name of the tala it is based on.

mobileslot.Evenweb.Com- Please let me know if you're looking for a article author for your site. You have some really great posts and I feel I wuld bbe a good asset. If you ever want to take some off the load off, I'd absolutely love to write some material for your blog in exchange for a link back to mine. Please send me an e-mail if interested.Thanks! my webb blog - mobileslot.Evenweb.Com

canadian pharmaceuticals online shipping- When someone writes an article he/she maintains the image of a user in his/her mind that how a user can know it. Thus that's why this article is great. Thanks!

-

Reply By Guruji-

In Ustad Enayat Khan ‘s time, many gats were composed almost following the base of a bandish, but it was done with abundant use of instrumental technique. Presently, in our gharana a gat is completely following the bols of concerned bandish without the use of plucked bols- i.e.,projecting the melody as it is sung. The structure remains the same as the gat follows the bandish verbatim.

-

Reply By Guruji-

Off hand, I can think of two reasons:

a. Great improvement in the quality of sitar, enabling greater resonance and ability to sustain greater gaps between phrases, and therefore slower tempo.

b. Increasing influence of khayal which reduced the tempo of execution of vilambit khayal, and similarly also influencing the playing of vilambit gat on sitar. Further, there are no set rules relating to the speed at which vilambit gat should be played. It would, in my opinion, be governed by the speed at which a player is able to execute chaugun taans. -

Reply By Guruji-

If we consider vilambit gat, then the player will have to regulate the pace according to his capability to play fast taans. If we consider the pace of alap, then it would have to suit the mood of the raga. Even the total length of alap could change depending on the capabilities of the player and the receptivity of the audience(?).

-

Reply By Guruji-

If we consider thumri-numa ragas like Pilu, Khamaj, Tilak Kamod etc., the vilambit gat is usually omitted unless one has the mijaz and capability to develop light classical music vistar. Otherwise what you mention would be correct. However don’t forget that classical music is governed by munde munde matir bhinna (different people, different approach/attitude).

-

Reply By Guruji-

Absolutely!

-

Reply By Guruji-

a. Masitkhani gats are played in slow or vilambit laya while the Razakhani gats are played in drut or fast laya.

b. Bol patterns are distinctly different. While Masitkhani gats have a clear distinct bol pattern, the Razakhani gats also have fixed pattern with a slight flexibility. Both gats are played only in Teentaal. The bols start from 12th matra. Razakhani gats also have a prescribed bol pattern which is also fixed but slight variations permitted according to the melodic mould of the related gat.

c. As mentioned, Masitkhani gats start from 12th matra. Also, as mentioned the Razakhani gats could start from the sam or khali or even the 7th matra of Teentaal. Both the gats are played only in Teentaal, though one of our past students had found some Masitkhani gats in Ektaal as well during her research on sitar.canada pharmaceuticals- Keep on working, great job!

pharmaceuticals online australia- It's amazing for me to have a web site, which is useful in favor of my experience. thanks admin

-

Reply By Guruji-

I don’t call gats that don’t follow Masitkhani bol patterns as Masitkhani gats. They are just vilambit gats. Similarly, gats which do not follow Razakhani patterns should be just called as drut gats. I also feel that Razakhani gats closely followed bandish ki thumri type of melodic structure to start with. We find this pattern in so many old Razakhani gats- both sitar and sarod gats. But later this changed partially because may be- due to the influence of gayaki ang in the instrumental music.

-

Reply By Guruji-

Why does a musician regularly practice paltas? – an interesting question with a normal answer – पलटा बजाने से गला या हाथ तैय्यार होता है | Then the next question would be ‘why’ – why through practicing paltas voice or hand becomes tayyar or dexterous with clarity?

After much thought, I felt that the real reason for practicing paltas and the ready answer ‘तैय्यार होता है’ has an intrinsic and psychological reason.

When one practices paltas, after playing the paltas for 15 – 20 times, the mind starts wandering with random thoughts. Then who guides the execution of paltas? The answer is that, it is the subconscious mind, which is involved in the actual execution of the paltas, while the thoughts in the conscious mind are somewhere else. In other words, it is by practicing paltas several times, the bifurcation of conscious and subconscious mind occurs. In reality, as only subconscious mind is executing the paltas, the outcome becomes effortless – we call the result tayyari.

Conclusion

The role of paltas is to ensure the bifurcation of conscious and subconscious mind, which enables the conscious mind to create music and subconscious mind to execute it. -

Reply By Guruji-

Apparently, riyaz is an Urdu word. Hence, the concept of riyaz, which is being followed presently, seems to be initiated by musicians following khayal style. As is well known, dhrupad follows a system derived from ancient traditions hence, though there are several common features, apparently different techniques are followed. (elaborate?)

Though, instrumentalists essentially follow khayal based system of riyaz, (elaborate) it is natural that instrumental techniques differ from vocal music techniques and hence there are some special features that the instrumentalists of sitar, sarod (plucked instruments) follow, are khayal based.

Great Ustads of our gharana – Ustad Imdad Khan, Ustad Enayet Khan, Ustad Wahid Khan, Ustad Vilayat Khan and the younger set are well-known for their intense and prolonged riyaz sessions. In fact, the gharana is well-known for great masters as role models of riyaz. To the best of my knowledge, I have not been able to listen any common features of riyaz practices followed by other different sitar gharanas.

What we hear is that great masters of our gharana used to continue riyaz based on the life of a lighted candle, which might take 2 to 2½ hrs. It is said that some of the Ustads undertook riyaz for 2 / 3 / 4 candles which would imply that they would practice anywhere between 8 to 10 hrs. To ensure disciplined practice, a system called chilla was followed which would ensure that the rigorous riyaz is continued for a specific period of usually 40 days.

What exactly they were practicing is not very clearly indicated, though it seems that they used to practice paltas made up of simple movements and perhaps some movements based on taan patterns.

My personal approach is based on my own experience. Practices of riyaz described earlier, as is evident, would result into greater control over the instrument. One important facet of the resultant effect was bifurcation of conscious mind and sub-conscious mind.

Hence I feel, as advised once by Ustad Amir Khan, “अरविन्दभाई पलटा बजाओ, (use this as a cue for next question) – रियाज़ करो but कुछ सोचो भी”, the process of ‘thinking’ is an additional element which in my opinion is of great value. Thus following one’s own thought while playing paltas with greater imagination. For this purpose, I have the following suggestion.

(Shouldn’t the student be experienced enough to be able to play?)

The student should play one raga from beginning to end as if he is playing in a concert before an audience. During this, the student will realize the area / section where he is confused or weak. The student should note these areas and with Guru’s advice, should concentrate on removing weaknesses based on techniques prescribed by the Guru. Further, by playing the same raga for a prolonged period like 6 months or so, the riyaz gets embedded into student’s mind and when he/ she plays the same in a concert, he/she would experience less tension, resulting in better creativity.

This suggestion is not with a view to replace paltas but in addition to the same. As already indicated earlier, we have structured four kinds of paltas, namely 1) simple paltas, 2) taan paltas, 3) raga vachak paltas and 4) bhav vachak paltas. Students have been taught these four types of paltas which they should practice regularly, consulting the Guru as and when required. Should we demonstrate?

In conclusion, I feel that there is no general prescription which could apply to all students. We have students from different sectors of the society. We have khandani students, we have professionals (like architects etc.), we have farmers, we have professional musicians, we have housewives who undertake taleem in addition to their own family responsibilities etc. Further, there are relatively highly educated students as compared to some others. Then some students write down or record taleem sessions and others would prefer to remember (as in the old system) and retain the taleem in their minds.

Hence, it is the responsibility of the Guru to prescribe the riyaz structure for each student keeping in mind the status of his/her education, cultural background, worldly responsibilities and other involvements.

Further to the above, I would like to add one important ingredient of riyaz, As is evident, several techniques of riyaz are mostly focused on the expression – in other words how to play.

It is equally important to learn what to play – content. For this purpose, my suggestion is that students should listen to as much music as possible, not only to have listening pleasure but also to accumulate the benefits of musical artistry.

-

Reply By Guruji-

Can content be extracted from a palta? and has? Further more are there paltas for techniques like gamak, meend, ghaseet, zamzama etc.

We have often discussed the role of paltas with our students.

The average response of the students was that, due to regular and strict practice of paltas, the voice / playing could achieve greater speed (tayyari) and thereby improve the quality of one’s performance. Hence, the practice of playing paltas has been considered to be a regular, indispensable part of riyaz. We have heard stories of musicians practicing paltas for hours and hours together for a long duration (chilla).

My question is how does practice of paltas improve the speed / quality of expression? It is a well-known fact that by practicing paltas for long periods, one gets greater speed (tayyari).

[ANP says that this following section is a repetition. How should it be dealt with?]

My contention is – when one practices paltas, after a few executions, the active mind starts wandering elsewhere whilst the voice / hand continues with paltas. How does this happen? When the conscious mind is not focused on paltas but is elsewhere, it is the subconscious mind, which takes over the actual execution of the paltas. It is also noted that the execution becomes tension free and hence easy and swifter.When conscious and subconscious minds are applied together for execution of paltas, there is tension and therefore it becomes a hindrance to achieve tayyari. In my opinion therefore, if the real role of paltas is to enable the musician to achieve speed, better quality etc., it will be possible through bifurcation of conscious and sub-conscious minds. My theory therefore is that conscious mind should create music and subconscious mind should execute.

-

Reply By Guruji-

The word gharana literally means a house (home). Different vocal music styles were called gharanas as each style was initiated by a family doyen. Each gharana has its own techniques of raga structure, its presentation, compositions and all other related techniques. In the following we list distinguishing features of each gharana.

Every gharana has an emotional undercurrent (rasabhav), which is the hallmark of the doyen of that gharana. Out of acknowledged 9 /10 rasas, according to musicians at large, rasas like karuna, hasya, shringar, veer, shanta etc. are used in musical expressions of different gharanas with varying emphasis.

Depending upon the rasabhav, the discernible features practiced by different gharanas would be as follows:

a. Preference for raga – shanta rasa pradhanya gharanas would prefer to sing ragas which project shanta rasa. Example, Bhairav, Todi, Puriya, Malkauns etc.

b. Preference for tala – different talas like Jhumra, vilambit Ektaal, Tritaal, Jhaptaal, Rupak etc. are selected by practitioners of different gharanas, according to their rasabhav. Example, shanta rasa based gharana would prefer compositions in Jhumra.

c. The voice production – would depend upon the undercurrent of the rasa, i.e. softer, louder, with a twang etc., would be the hallmarks of different gharanas. Examples, hasya rasa based gharanas would generally sing with an open throated voice while shanta rasa pradhan gharanas would prefer softer and subdued voice.

d. Raga elaboration (unfoldment) would depend upon the temperament of the doyen of the gharana. Some gharanas do not have lengthy unfoldment of the raga – whilst some gharanas unfold the raga in a very detailed manner and develop the raga structure in a very leisurely manner.

e. Taan variety – each gharana has developed the structure of taans specific to their style. Usually the pattern / structure depends upon the initiation by the moolpurush of the gharana.

f. Importance of bandish presentation – several gharanas give tremendous importance to the presentation of the bandish / composition and have specific rules to present the same.Gharana system is an attempt at specialization of the tenets relating to different styles of vocal music. In dhrupad singing, such distinctions are known as banis, for example, Gauhar bani, Dagar bani etc. Apparently they are not as distinct from each other as in case of gharanas.

With regard to instrumental music, there are various gharanas. In the art of tabla playing, there are distinct gharanas like Delhi, Ajrada, Farukhabad, Banaras etc. In sitar, there are some distinct names like Maihar gharana, Etawah-Imdadkhani gharana, Vishnupur gharana etc. Similarly there are nomenclatures of sarod style. For instruments like flute, santoor etc. the styles do not appear to be identified with the name of the gharana.

-

Reply By Guruji-

While describing the physical and stylistic evolution of the sitar, we have traced its history from the sitar being used as purak instrument during qawwali recitals. Over a period, a lot of changes were made by different maestros including Ustad Imdad Khan, especially related to the expression of the presentations.

Imdad Khansaheb developed his right hand execution with amazing speed and accuracy. Though, the left hand was dexterous, it was treated with a lesser importance in the Imdadkhani baj. From his recordings, we note the highly right hand oriented bols with amazing speed and clarity. As far as the content is concerned, Imdad Khansaheb was involved with playing a few ragas though he would have known many ragas. It is believed that Puriya and Yaman were his favourite ragas.

Ustad Imdad Khan gave great importance to riyaz. His disciplined and meticulous riyaz has been talked about with awe and respect. It is believed that, once he started his riyaz with a lighted candle as a measure of time, his daughter was on her deathbed – subsequently she died, but Imdad Khansaheb did not break his riyaz until the candle, which was the measure of time, was completely burnt out.

It is in the later period of Ustad Vilayat Khan, that the Etawah–Imdadkhani baj became a perfect amalgamation of both right hand and left hand – it was Ustad Vilayat Khan who perfected the gayaki ang, though seeds of which were laid by Imdad Khansaheb.

-

Reply By Guruji-

a. There has been a firm belief that musicians were expected to play only dhrupad ang on veena and surbahar.

b. However, on listening to several recordings of Imdad Khansaheb and Enayet Khansaheb on surbahar, and also listening to the radio recitals of veena of Ustad Sadiq Ali Khan and Ustad Asad Ali Khan, it is noted that, they were not involved with pure dhrupad ang – but had a flavour of khayal ang in their recitals.

c. On enquiring with Ustad Vilayat Khan, whether it is appropriate to play surbahar and veena etc. partially based on khayal ang, his reply was that, khayal ang on surbahar was quite distinct as compared to the khayal ang adopted for sitar recitals. In one of his archival recordings at the NCPA, he has demonstrated the difference.

d. It is therefore surmised that khayal ang on surbahar and veena could be based on the following tenets:

i. Executing phrases rather than single note development (as in dhrupad)

ii. Swift movement between two or more notes should be executed with a certain amount of lehek and not with a jerk– as in khayal.

iii. Murkis played on sitar should be avoided. However, murkis could be executed in much slower meend like movements. Jhapkis should be completely avoided.

iv. Only one kan (as in dhrupad) is permitted – though later we find regular murkis being practiced but as mentioned above, only in meend like slow movement and not sharp movement as in regular murkis. -

Reply By Guruji-

a. I would like to advise as follows:

A musician prefers to project / execute his musical expressions essentially depending upon his own aptitude. (I am a bhakti margi and hence prefer an inward looking slow pace of alap)

b. The aptitude of a person depends upon several factors, some of which are:

i. Family Culture – a child absorbs the culture of the family and develops an aptitude in keeping with what he has inherited.

ii. A person is influenced by his environmental factors apart from his own family. One is affected by friends, educational institutions where the person is studying and been exposed to many influences, listening to difference kinds of music (great exposure to YouTube) etc.

iii. One develops a temperament depending upon which community he is born in. Different communities have different mental approaches to life and the child therefore is influenced by the same.

iv. It is well-known that with advancing age, one develops maturity over the years. This process results in evolving aptitudes at different stages of one’s life.

v. We all believe that a musician is not “made” in one lifetime and hence one’s aptitude depends also on the musical experience which one carries over from one’s previous life/lives.c. It is true to say that the pace of alap – infact the entire presentation is related to the rasabhav of that raga. Hence the pace or even the length of the alap in ragas like Malkauns, Todi, Bhairav etc. would be much slower than the similar execution in ragas like Shankara, Hansadhwani, Bahar etc.

d. Guru’s taleem – It is not unusual to change one’s approach to music based on the taleem he has received from his Guru. Over a period of time the shagird is influenced through regular taleem sessions on lines of approach of his Guru, for whom he has tremendous respect and devotion. Thus aptitude changes, which results into preferred pace of alap.

e. Financial constraints – It is well-known that “classical” music has become “massical” music, as a result of which, the musician is constrained to adapt presentations to suit common public preference. Though his recitals for certain audience may project introspective approach, on several occasions, the pace of the entire presentation (including alap) is more related to the popular taste.

f. As a corollary of the above, influence of fusion – popular – exciting – thrilling music results into “entertainment” which the public at large these days desires. Opportunities to play authentic or undiluted music in today’s world of massical music are becoming difficult as opportunities for popular music are far in excess of opportunities to present pure classical music.

-

Reply By Guruji-

With regard to influence of gharana as referred in the question, I would mention that gharanas like Kirana (vocal), Farukhabad (tabla) have different streams, each of these have deferring aesthetic values. Even within a gharana, different Ustads / Gurus might similarly have different aesthetic approach depending upon several factors mentioned by me. Hence, I thought it proper to refer to influence of individual Ustad / Guru rather than referring to influence of gharana.

-

Reply By Guruji-

a. A teacher takes responsibility for your growth. A Guru makes you responsible for your growth.

b. A teacher gives you things you do not have and require. A Guru takes away things you have and do not require.

c. A teacher answers your questions. A Guru questions your answers.

d. A teacher requires obedience and discipline from the pupil. A Guru requires trust and humility from the pupil.

e. A teacher clothes you and prepares you for the outer journey. A Guru strips you naked and prepares you for the inner journey.

f. A teacher is a guide on the path. A Guru is a pointer to the way.

g. A teacher sends you on the road to success. A Guru sends you on the road to freedom.

h. A teacher explains the world and its nature to you. A Guru explains yourself and your nature to you.

i. A teacher gives you knowledge and boosts your ego. A Guru takes away your knowledge and punctures your ego.

j. A teacher instructs you. A Guru constructs you.

k. A teacher sharpens your mind. A Guru opens your mind.

l. A teacher reaches your mind. A Guru touches your spirit.

m. A teacher instructs you on how to solve problems. A Guru shows you how to resolve issues.

n. A teacher is a systematic thinker. A Guru is a lateral thinker.

o. One can always find a teacher. But a Guru has to find and accept you.

p. A teacher leads you by the hand. A Guru leads you by example.

q. When a teacher finishes with you, you celebrate. When a Guru finishes with you, life celebrates.

Let us honor both, the teachers and the Guru in our lives… -

Reply By Guruji-

Intuitively, I feel that these two ragas viz. Bageshree and Kanada do not seem to gel.

Let us see phrases of both these ragas which in my opinion do not match:

a. Bageshree goes with Ma-Ga (komal)-Re and Kanada goes with Ga (komal)-Ma-Re.

b. Phrase Dha –Ni (komal)-Pa has shuddha Dha as in Bageshree while komal Dha in Kanada No doubt Ni (komal)- Pa-Ma-Pa is a Kanada phrase but it does not match with Dha-Ni (komal)-Dha Ma-Pa of Bageshree. In any case komal Dha is just not used indicating Kanada ang.

c. Ni-Pa-Ga (komal) (with a ghasit of Kanada) do not match with Dha-Ma-Ga (komal) of Bageshree.

d. Some musicians use the phrase Sa-Ga (komal)-Ma-Pa as in Bhimpalas with Pancham as a resting point to indicate Kanada, which I think is unsuitable.I find that the mood of Bageshree and Kanada also have a differing approach. It is not easy to define what sentiment raga Kanada conveys, as there are so many prakars having deferring undercurrent (rasa). I find Bageshree on the other hand, has a mood of shanta rasa in purvang and adding Pancham and a touch of shringar in the middle octave. Hence your 2nd question- how to balance between Bageshree and Kanada becomes irrelevant in view of what I stated above.

Sankirna ragas are matched in 3 ways:

a. one raga in arohi (asect) and another raga in avrohi (descent)

b. one raga in purvang and another raga in uttarang

c. mixing of ragas without any specific framework meandering during execution to slip from one raga to another.

d. Frankly, I do not find anything worthwhile to balance these two ragas as there are so different.

When you consider my above remarks, response to your question no. 4 becomes unnecessary.

However, melodic movements of Shahana Kanada and Bageshree Kanada are so different. In Shahana though it is known as Kanada, I don’t find any marked flavour of Kanada. -

Reply By Guruji-

Every raga has Sa as the base note. Chikaris are meant to sustain this element, hence both the chikaris are to be tuned in Sa. Last one should be in upper Sa and other in the basic Sa.

https://Penzu.com/p/c961de29- I'm really enjoying the design and layout of your website. It's a very easy on the eyes which makes it much more enjoiyable for me to come here andd visit more often. Diid you hure out a developer to create your theme? Great work! Feel free to surf to my weeb page ... https://Penzu.com/p/c961de29

-

Reply By Guruji-

In Puriya, both strings should be tuned in Ga. While in Marwa, they should be in Dha and Ga (from chikari side). These selected notes are the vadi-samvadi notes of the respective ragas.

-

Reply By Guruji-

Yes, at the risk of being contradicted.

-

Reply By Guruji-

a. To start with, I would like to mention that all the surbahar recitals that I have heard hitherto, have been played with alap, jod and jhala. These surbahar players did not play gats at all. To name a few, Ustad Imdad Khan (Jaunpuri record), Ustad Enayet Khan (several Surbahar records), Ustad Mushtaq Ali Khan (Puriya full national program) – no gats. Even Ustad Vilayat Khan, Ustad Imrat Khan or Shri Pushparaj Koshti did not play any gats. Some of them played gats on the sitar as a follow-up.

b. Hence, to play gats on surbahar is a concept unknown to me. However, if we wish to play gats within the surbahar recital– as have been played with Been / veena, we could think about a little modification and follow the been pattern (with pakhawaj accompaniment).

c. Dhrupad bandishes (not gats) played with Been follow the dhrupad idiom – perhaps with the slightly faster tempo. I have composed a short bandish in Jhaptaal. This composition follows dhrupad rendition but with khayal ang. Hence, if it is desired to include a gat composition in a surbahar recital, I would recommend that it should be done in Jhaptaal or Sultaal. The actual composition could be based on a dhrupad composition sung in this tala, which might be termed as sadra.

d. Ustad Vilayat Khan had mentioned in his NCPA recordings of rudraveena (been) that, Ustad Sadiq Ali Khan, Ustad Asad Ali Khan etc. leaned a lot on khayal ang in the bandishes played with pakhawaj.

e. It is self-evident that, if bandishes / gats are to be played on surbahar, it will have to be accompanied by pakhawaj and not tabla – tabla would give a distinct khayal based tempo.

f. The development of bandish / gat in such a case will have to follow the sitar gat unfoldment upto the stage of gat-kam, just as taan patterns are not a part of dhrupad rendition.

g. Hence, jhala could be played just as we play in sitar recitals except (I assume) that, in the alap / jod stage, jhala portion consisted of ulta-jhala. In conclusion, we would add that sobriety and introspective element of surbahar should not be lost in an attempt to play aggressive rhythmic patterns.

-

Reply By Guruji-

Kachhuva is known as kachhuva sitar and not kachhuva been (rudraveena). From historical record, it appears that kachhuva sitar is somewhere in between the instruments surbahar and normal sitar. The name comes from kachhuva or a tortoise, as the lower part of the tumba is akin to the upper surface of a tortoise. To my mind, there is no other similarity, though the name kachhuva sitar has continued over the centuries. I have heard kachhuva sitar only once in my life. I was too young to discern the differences of sound and plucking technique of a kachhuva sitar as compared to a surbahar. It is evident therefore that, the instrument seems to have disappeared, as it had no worthwhile and unique characteristic, which could add in any substantial manner to the existing Indian instruments like surbahar and sitar.

-

Reply By Guruji-

Referring to Allyn Miner’s book on sitar and sarod, it is noted that sarod was conceived by one Ghulam Ali Khan Bangesh in the first half of 19th century. It is an accepted theory that sitar was invented by Fakir Khusrau (belived to be the brother of Sadarang – Niyamat Khan) in the 18th century. Thus, it appears that sitar was invented before sarod

-

Reply By Guruji-

Your query with regard to my musical experience of listening to music greats in the past, requires a longish response as follows:

I had the opportunity of listening to Ustad Bade Ghulam Ali Khan prior to listening to Ustad Amir Khan, Begum Akhtar and Ustad Faiyaz Khan.